all-in-one-seo-pack domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/gerryspence/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6114

My father contended that the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission set the opening day of deer season so that the rich, who didn’t have to work for a living, could enjoy the hunt unencumbered by the horde of working men who would otherwise be taking to the field. In those hard times men worked six days a week. On a Sunday, the second day of deer season, my father drove us in our Model A Ford to Little Goose Creek where he said he knew of a secret herd.

My excitement made it hard to breath. I couldn’t talk and my father wasn’t one to say much either. I remember him slapping my leg and smiling at me. The leg slap meant we were together, a couple of men on a hunt, which was among the highest callings of the species. To my father, hunting trumped churching. A man ought not suffer stuffy, man-made churches in deer season when he could go into God’s own perfect church, the out-of-doors, and in the process, bring home some venison.

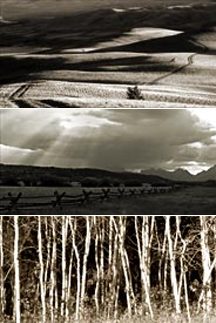

It was just getting light, say, a little past six, when we arrived at Little Goose Creek. Suddenly my father brought the Ford to an abrupt halt. He nodded toward a grove of quaking aspens, and there, in the dim early morning I could make out the white rumps of a small herd of mule deer. My father eased out of the Ford and silently beckoned me to do the same. With a finger to his lips he admonished me to close my door quietly. He lifted his rifle from the back seat and handed me mine. At the barbed wire fence, and for safety, we slipped our unloaded rifles under first. Then we crawled through and loaded our guns. I was shaking. He looked at me and whispered, “It’s O.K, it’s just buck fever.” But the deer and the cold morning and buck fever were not the only cause of my trembling. There, on the very fence post where we crawled through, was a sign that read, “No hunting or trespassing. Violators will be prosecuted.”

Following the outer edge of the aspen grove and in a crouch my father walked quickly toward the grazing deer. When we were about fifty yards from the herd he eased down and made a motion for me to do likewise. We lingered for a moment, our breaths making those small clouds like steam from an almost boiling kettle. Then my father leaned over and whispered, “Pick out a dry doe.” There were no bucks in the herd. A dry doe was one that had no fawn at its side. I looked and quickly chose the largest doe in the herd. He whispered further instructions. “Take your sitting position. Be sure your gun is off safe.” I did as he said. I was taking small short breaths like a pup panting in July. “Now aim just above her elbow(that’s where the heart lies. Ok. Now hold your breath. Don’t close your eyes. Hold steady. Now squeeze the trigger nice and slow.”

Then the explosion!

The doe fell like a dropped sack, rolled over on her back, and kicked at the air a few times in death spasms. My father ran to her, I a couple of yards behind. He pulled his hunting knife from its scabbard, sliced her belly open, and with great skill and dispatch extracted her enthralls. Then he handed me his rifle to carry while he quickly drug the carcass to the car.

Once back in the Ford, the doe safely in the back seat on a canvass cover, and the old wreck rattling toward home again, we were finally able to speak.

“That was a good shot, son,” he said.

I was proud. But something was bothering me. Finally I asked, “Dad, what about that no trespassin’ sign? Weren’t we violatin’ the law?”

“Well, son,” he said, that land belongs to a rich English remittance man,” as if that were a complete answer. A remittance man, as he later explained, is a son of some wealthy lord in Britain where primogeniture prevailed so that the eldest son inherited the entire estate of the parents. So what do you do with the middle kids? You get them out of the way by shipping them off to Wyoming or some other frontier, give them enough money to buy up the choice land along wonderful trout streams and send them a check every year(their remittances(to live on.

“But how come we trespassed?”

“Well, son,” he said looking down the road as if he saw a vision, “the rich man owns the land. But the people own the deer.” He looked over at me as if I should understand. That insight didn’t mean much to me at the time, but later as I became a part of the legal system I learned that the law is often not just. It is just the law.

“Weren’t you afraid they’d catch us?” I asked.

“Those kind never get up that time of the mornin’, he said.

And something else I learned. That doe I shot didn’t have a tooth in her head. She was old and tough, and although my mother pounded her steaks until they were nearly hamburger, her meat remained stringy and nearly inedible. “Besides,” my father said as I chewed endlessly on a piece of her steak, “chewing is good for your jaws.” Then he grinned and winked at my mother.

But the unyielding principle my father taught us was that we eat what we kill. And we ate every last ounce of that old doe right down to her liver and her heart. Wasting any part of her would have been a sin of the worst order( something approaching murder although there was no law that said you had to eat what you killed. The doe had given up her life to us. There was a holiness about that they didn’t teach in church.

I learned from my father that ethics exist independent of the law. I’ve never needed the law to tell me what was right or wrong, nor the church nor any guru nor anyone else. Often those who render judgments against us are wrong. Although we are bound by the law, and by the values of a decent society, I learned from my father that the final judgments on the choices we make are judgments rendered by the self in a courtroom in which the self is on trial and the self, a most formidable judge and jury, hands down its verdict.